Handlers and Dogs Compete at Soldier Hollow Contest

By TONIA ANDRUS FULLER

Sheep Industry News Contributor

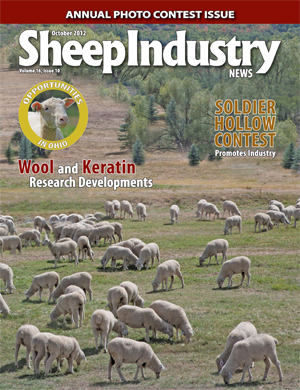

(Oct. 1, 2012) Long known as man’s best friend, 64 border collies proved they are even more at the 10th Annual Soldier Hollow Sheepdog Championships in Midway, Utah. This international invitational tournament, held Aug. 31-Sept. 3, hosted contenders from five countries. They and their excellent dogs competed for gold, silver and bronze medals at beautiful Soldier Hollow, a former Winter Olympic Games Venue in the Wasatch Mountains 45 minutes east of Salt Lake City.

The event attracted more than 25,000 spectators across the four days of competition. As they watched the sheepdog and handler work the sheep, they listened to the announcer talk about the benefits of wool clothing, the cycle of range sheep, why sheep grazing is good for the environment and that lamb is natural and delicious.

The Promotion Committee of the Utah Wool Growers Association was the first sponsor of the event 10 years ago, and continues to sponsor the International Food Court, where American lamb is featured in enchiladas, burritos, kabobs, brats, burgers, meat pies and a Greek dinner plate.

“Over 40 percent of those who eat here try lamb,” says Mark Petersen, event director. “It’s in the spirit of being at the event. People will eat lamb in this setting, who wouldn’t normally try it.”

Attendees also watched Navajo rug weaving demonstrations, learned how to cook lamb Dutch-oven style with a Camp Chef, and purchased in record numbers Woolrich wool blankets and other wool clothing items.

To promote the event, there were many interviews and lamb cooking classes on Utah’s local TV news programs, radio ads, newspaper ads and more than a dozen event sponsors offering discount tickets. Promoting the sheep industry is not a passive activity, it is a real focus of the event, says Petersen.

Veteran Utah sheep producer, Lee Jarvis, loves to see the intelligent, well-trained dogs and believes each year the attendees come away with a favorable impression of the sheep industry.

“In this beautiful setting, you have thousands of people who get a positive connection to wool growers. People are introduced to lamb and wool that may not have ever experienced it before,” says Jarvis.

And of course, there is the excitement of the competition. As the spectators watch, some with binoculars, they cheer as the dog brings the sheep through a gate, groan as a defiant ewe gets off course, give a collective, understanding laugh as a young dog leaves the sorting ring for a quick cool off in the temptingly-near water tub at the dog cooling station. They develop favorites who they hope score in the top five to get into Monday’s finals.

There were 44 ‘handlers,’ as the human half of the sheepdog team is referred, some with two dogs entered. As you visit with the handlers, you get a sense of camaraderie and community. They know each other and the dogs well. They get along, visit, cheer for each other and say that the good people they associate with is one of their favorite aspects of competing. Most handlers at this level travel across the country to dog trials each month, and at Soldier Hollow — an invitational tournament for veterans or up-and-comers who have proven their abilities — they know each other pretty well.

All of the handlers own sheep, from 16 head up to thousands of head. Some handlers grew up herding sheep, others purchased them for practice after getting involved with sheepdog competitions. They all say experience with and understanding sheep is a key part of success in sheepdog competitions.

Utah handler Libby Nieder says practical work experience leads to a well-rounded dog. In addition to working her own sheep, she helps other ranchers in the summer, working sheep on the range and in the corrals.

Patrick Shannahan, a handler from Idaho who trains dogs for the livestock industry, laments that they are losing some of the ranching aspect.

“People used to come into (the dog trials) through livestock experience, but now many handlers come in from the dog training side,” Shannahan says.

Jack Knox has been working with sheep and dogs all of his life. He began as a shepherd in Scotland, and came to North Carolina in 1971 to work on a ranch in North Carolina. He now lives in Missouri with his wife Kathy, the only husband and wife to have both won national championships in the world.

Knox says a border collie can do the work of two men on a ranch, but many sheep men today don’t understand their potential or how to best handle them. He has presented stock dog seminars to livestock producers, but wishes there was greater response and use of sheep dogs.

“(Ranchers) say they are too busy working to come to the seminars. And now they race around (on their ATV’s.).”

Edd Sabey, a Utah sheep shearer, agrees that the 4-wheeler has played a role in the decline of the trained sheepdog. “You used to send out your dog, then go saddle your horse and meet up with him after he had gathered the herd. Now they’ve lost patience. They just jump on their 4-wheeler and have to go.”

One sheep producer who caught the vision is Laura Pearson of Kemmerer, Wyo. She runs 2,500 Finn/Targhee ewes, and says sheep dogs are the only way to go out on the range. She always had border collies, but only after she attended one of Knox’s clinics did she reach the level where she always brings a dog with her in the truck, and leaves the rope, the horse and the trailer at home.

During finals, Pearson watched Knox and his dog Jim work the sorting ring, separating five ewes with red collars from the other 16 sheep. They do so quickly and efficiently, then Knox runs to open the gate, leaving Jim to bring the sheep in for the final pen. With baited breath, she and her kids watched as one ewe looked like it would bolt past the gate. But Jim and Knox smoothly work them in, and close the gate, stopping the clock. Ecstatic cheers erupted.

Knox’s usual calm reserve is broken by a joyful grin and he throws his cap in the air, to more applause. He praises Jim as they walk to the cooling tub. Their score of 141 puts them in the lead, and will carry them on to the gold medal stand, as winners of the Soldier Hollow Classic.

Dee Sabey and his brother Edd provide the hay for the 300 sheep used in the four-day competition. Sabey says coming to the Soldier Hollow Classic has become a great tradition. “It gets in your blood, kind of like sheep,” he said.

That despite the fact that one year, about 20 head of sheep escaped up into the hills during the competition. The hills are pretty steep and covered in juniper, brush and scrub-oak. Soldier Hollow stockman Doug Livingston said the Sabey brothers helped him bring the sheep in, but when they returned their shirts had been shredded to nothing from chasing through the brush.

Experiences like that must be what South African sheep rancher and competitor Faansie Basson had in mind when he responded to this question: What is your favorite part of working with sheepdogs? “You don’t have to walk up the hill yourself,” he joked. Or at least walk up the hill alone.

Sheep Dog Trial Rules

Sheepdog competition is rooted in the tradition of taking good care of the stock. Each contestant starts with a set amount of points and a judge deducts points for faults and errors, including variations from the rules and mishandling of the sheep.

The Soldier Hollow Classic open trial consists of the Outrun, the dog leaves the handler to get behind a group of five sheep who are up the hill 400 yards away. The dog takes control of the herd and gets them on the move (Lift) and begins the Fetch, bringing them through a gate and behind the handler. Next the Drive, taking the sheep out away from the handler in a triangle formation through two gates, and back for the Shedding. During this time, the handler has to stay at post position, but once the sheep are in the shedding ring, a circle marked by red bean bags, the handler joins the dog to separate off two sheep, while maintaining control of the others inside the shed. Finally in Penning, the handler heads to open the pen gate, the dog brings the sheep and works them into the pen. Time ends when the gate is closed. Twenty four minutes are allowed for the course.

For the International Double Lift Final on Labor Day, the top five competitors of each previous day face a more challenging course, with 175 points possible. The dog must bring in two separate groups of eight sheep, one with red collars, through the gates, and then join the herds together before taking them through two gates and back to the sorting ring. In the sorting ring, dog and handler work together to separate off all but five sheep with red collars. If at any point there are less than four sheep with red collars in the ring, the whole herd must be gathered back in the sorting ring to begin again. Then on to the final penning as with the open trials.

Meet the Sheep

Over 300 head of sheep are needed for the competition, and they are supplied by John and Charlie Young of Brigham City, Utah. The 15-month-old Rambouillet and Columbia ewes were brought in off the summer mountain range with the help of Doug Livingston, head stockman at Soldier Hollow, and they spend long hours making sure the sheep are as sound and consistent as possible. The truck driver Jamie Sweat, said this group was the hardest to load he’d ever had, a fact shared among the competitors, who know that it just takes one stubborn or independent ewe to tip the competition.