- April 2016

- President’s Notes

- ASI Legislative Trip

- Sage Grouse Discussion

- Changes for Price Reporting

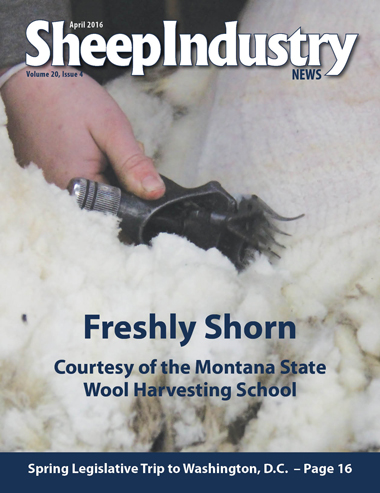

- Shearing 101 in Montana

- Science of Bighorn Report Questioned

- USSES Reports Available

- American Lamb Board Vacancies for 2017

- Market Report

- NLFA Leadership School in Ohio

- Sheep Heritage Foundation Scholarship

- Around the States

- The Last Word

Science of Report Questioned

Montana Bighorn Report Has Serious Flaws

THEODORA JOHNSON

Western Livestock Journal

“Separation of domestic and bighorn sheep is vital to ensuring bighorn herd health,” begins a recent report out of Montana. The report, which seems to have been a joint effort of the National Wildlife Federation, the Montana Wildlife Federation and the Wild Sheep Foundation, proposes a 20-mile buffer of separation between bighorn sheep and domestic sheep.

The alleged reason: Pneumonia transfers from domestic sheep to bighorn are leading to massive die-offs of bighorn herds across the West. Because some bighorn rams have been observed to wander up to 20 miles from the herd’s established range, the groups claimed that a 20-mile buffer zone would be appropriate.

“The report mentions a number of private landowners and producers, from commercial sheep operations to 4-H and FFA kids’ livestock projects,” said ASI Executive Director Peter Orwick. “Montana’s sheep producers would be right to feel targeted.”

Indeed, the report pinpoints specific domestic sheep operations, including 47 production herds on private land, 66 federal sheep grazing allotments, 11 “hobby flocks,” six sheep weed-control projects and parts of Montana State University’s Red Bluffs Ranch. The report goes so far as to give the specific location of every operation it deems a threat.

Although the report calls for various voluntary actions on the parts of producers to prevent bighorn/domestic contact, Orwick said the report “reads very intimidating to me.”

He added that reports such as these, if taken seriously by the federal agencies, can have dangerous policy implications.

In fact, Orwick told WLJ that the U.S. Forest Service is already using flawed “risk assessments” regarding disease transmission between bighorns and domestic sheep. He cited an example in Idaho, where USFS used a risk-assessment model in a 2010 decision to remove 70 percent of the domestic sheep from the Payette National Forest. Because of the model’s nine-mile buffer zone, roughly 10,000 head were removed, putting several ranches out of business and severely downsizing others. Applying this model West-wide threatens a quarter of the domestic sheep industry, Orwick said.

There could be implications for sheep herds on private land, too, Orwick stated. The Alaska chapter of the Wild Sheep Foundation has been pushing a policy that would require all domestic sheep and goat owners in Alaska to have a permit. Sheep and goat owners located within 15 air miles of Dall sheep (close relatives of bighorn) would be required to double-fence their property. Goats and sheep would be required to be “certified disease-free when testing becomes available,” the wild sheep proposal reads.

Science Challenged

What if the disease transmission assertion were a fallacy in the first place? Leading scientists in the realms of epidemiology, pathology, and infectious animal disease are, in fact, making that claim.

Dr. Mark Thurmond is Professor Emeritus of Veterinary Epidemiology at the University of California, Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine. He has been studying and teaching infectious disease epidemiology for over 40 years. He said the transmission of pneumonia between domestic and wild sheep is “an impossible disease concept.”

“When it comes to infectious diseases, there’s a mistake you cannot make: confounding disease transmission with disease agent transmission,” said Thurmond, who is also former co-director of the Center for Animal Disease Modeling and Surveillance at the university.

Pneumonia is a complex disease and is due to a complex series of events and exposures, he said. That includes exposure to disease agents such as bacteria, but it also includes stressors such as extreme weather, predation, overpopulation or nutritional changes. That stress releases stress hormones in the animal, which weakens the immune system.

“Then the bacterial agents – mycoplasma that are normal residents in the respiratory tract and nasal passages – begin to grow unchecked, because the immune system can’t fight them back,” said Thurmond.

In short, pneumonia can’t be transmitted, only the agent can be transmitted. Making that differentiation might seem like splitting hairs, but it’s important to the discussion surrounding domestic/bighorn separation, said Thurmond. There are far more factors at play than simply transmission of agents. This is evidenced by the fact that there have been numerous observed contacts between domestic sheep that weren’t followed by die-offs of bighorns. He added that there have also been numerous die-offs when no contact was observed with domestic sheep or goats.

WLJ also spoke with Dr. Maggie Highland, a veterinary anatomic pathologist and infectious disease researcher with the Animal Disease Research Unit of the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service. She, too, pointed to areas where domestic sheep and native bighorn sheep continue to thrive side-by-side. She asserted that, in some cases, bighorn have thrived even in the presence of the primary agent for pneumonia, a bacterium called mycoplasma ovipneumoniae. She also pointed out that mycoplasma ovipneumoniae is endemic to North America, meaning it’s a constant that’s not likely to go away, regardless of what wildlife managers do.

“The oddity of this all is the fact that mycoplasma ovipneumoniae is an endemic agent in North American small ruminants,” Highland said, “yet there is a desire to make wild small ruminants completely free and naïve of exposure to this bacterium. It has become policy in some cases to kill (shoot) survivors of herds that experience outbreaks of pneumonia – I know of a case in which just over 200 surviving animals were killed – then bring in new bighorns to repopulate the area, without really understanding all of the factors that caused the first outbreak.”

She said rather than attempt to maintain bighorn herds that are mycoplasma free, the agencies should be trying to find ways to help bighorn live with the presence of this bacterium. “I think the key to the problem lies in understanding why the survivors survive,” she said.

She listed possible efforts such as reducing human-imposed stress, focusing on nutrition and controlling population size.

Orwick told WLJ that, if agents such as mycoplasma ovipneumoniae are endemic, killing animals that are survivors, and possibly genetically resistant, would appear to be a misguided policy.

“Destroying an entire industry just to avoid transmission would also be an obvious mistake,” said Orwick.

A Push for Scientific Integrity

Thurmond recently wrote a paper pointing out some of the flaws in two of USFS’ risk assessments regarding bighorn/domestic separation. Those USFS risk assessments were for Idaho’s Payette National Forest and Colorado’s Snow Mesa region.

“Review of [the risk assessments] reveals an absence of key steps, ‘best available science,’ and ethics required in [risk assessments] and modeling, and in science in general,” Thurmond wrote.

He gave examples of some of the “more egregious issues.” For example, the Snow Mesa risk assessment makes several statements claiming domestic sheep transmit disease to bighorn, citing “Besser et al. 2012, Cassirer et al. 2013” as research references. The problem is, neither of those bodies of research actually supports that assertion, Thurmond wrote.

“Neither publication presents any methodology or results for ‘transmission of respiratory disease,’ nor did either examine any domestic sheep as study subjects,” Thurmond wrote.

“Similar false testimonies persist throughout the… [risk assessments]. Such significant misrepresentation of published results is a serious scientific offense and violation of trust,” he wrote.

Thurmond told WLJ that government agencies would be less likely to continue to operate on faulty science if they were to follow guidelines laid out by the National Academy of Sciences.

“In 1983, NAS published guidelines for the science of risk assessment, referred to as the ‘Redbook,’” Thurmond said.

The Redbook guidelines include standards on “dose, exposure and probability of transmission,” he said. He added that the forest service followed none of these guidelines in the two risk assessments he analyzed.

“If the industry groups would rally together and demand that the agencies follow the Redbook guidelines – on every decision – we could avoid much of the damage that results from government policies that lack scientific integrity.”