- April 2016

- President’s Notes

- ASI Legislative Trip

- Sage Grouse Discussion

- Changes for Price Reporting

- Shearing 101 in Montana

- Science of Bighorn Report Questioned

- USSES Reports Available

- American Lamb Board Vacancies for 2017

- Market Report

- NLFA Leadership School in Ohio

- Sheep Heritage Foundation Scholarship

- Around the States

- The Last Word

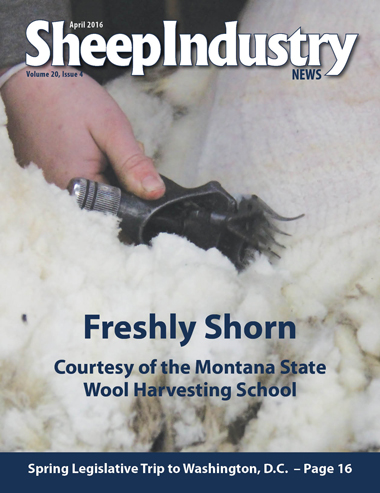

Shearing 101 in Montana

Three-Day School Draws a Variety of Students

KYLE PARTAIN

Sheep Industry News Editor

Farm flock owners, college kids and those with an eye on turning pro one day were all among the students at the annual Montana State University Wool Harvesting School on March 19-21 at the university’s Red Bluff Research Station near Norris.

Surrounded by professional shearers – who’d just finished shearing at Montana rancher Jerry Paugh’s place the day before – the students overcame the No. 1 fear that plagues nearly every one who’s stood in their inexperienced shoes for as long as shearing schools have existed: the handpiece.

Surrounded by professional shearers – who’d just finished shearing at Montana rancher Jerry Paugh’s place the day before – the students overcame the No. 1 fear that plagues nearly every one who’s stood in their inexperienced shoes for as long as shearing schools have existed: the handpiece.

With experience comes the ability to masterfully plow through a fleece blow after blow without leaving a single mark on the sheep in their hands. Inexperience leads to a timid stroke that simply won’t get the job done.

“Being scared of the handpiece and cutting the sheep is the biggest fear they all have,” says experienced shearer Ryan Keyes, who served as one of five official instructors at the school. He was joined by Mike Schuldt, Ralph McWilliams, Brent Roeder and Ben Roeder. Several other experienced shearers were also on hand and offered their expertise when necessary. “Once they get comfortable with how the handpiece works and how to make a smooth blow down the sheep, then they’re usually ready to really start learning the process.”

There’s definitely a learning curve to getting comfortable, however. Much like a guy shaving his face or a woman shaving her legs, the occassional glitch in the process amounts to no more than a nick.

The school began with a session on animal welfare and handling, aspects of shearing which are just as important as learning to use the handpiece. Sheep have to be sheared for their own safety and comfort, but the process needs to be conducted in a manner that causes the least amount of stress on the animals.

From there, students headed straight to the shearing barn. After all, there’s only so much of the process that you can learn sitting in a classroom. Schuldt provided instruction on tagging – removing wool from the sheeps’ heads and tails – and set the students right to work. Three students and an instructor were assigned to each station.

“Tagging is a great place to get started,” Schuldt says. “It gives the students a chance to get comfortable with the handpiece before we start shearing the whole sheep.”

The school’s 16 students spent several hours tagging before lunch on the first day. Then it was time to step up the challenge a bit. Instructors handled shearing the body of each sheep after lunch, but stopped short of the final four or five blows. They turned those over to the students, who got their first real taste of shearing the valuable fleeces produced by the university’s Rambouillet and Targhee flocks.

“There’s definitely a learning curve,” said Siri Larsen of Eureka, Mont. “But you can’t be afraid of the process. You just have to go for it and know that you’re not going to hurt the sheep.”

Larsen runs a mixed flock of about a dozen sheep back home. Originally her husband planned to attend the school, but the couple decided he had too much on his plate.

“So, I’m here instead,” she says. “I’m a spinner and a knitter and we have a hodgepodge of sheep because I wanted to try different fleeces. I’d like to learn the whole spectrum of caring for the sheep, from beginning to end and shearing is a big part of that. I’d like to be able to do that myself.”

While Larsen might not always shear her own sheep, she wants to know that she can do it if the need arises.

“The shearers only come through our area once a year, and that’s not always the best time for us to shear,” she says. “Some years we might have them do it, but I need to be able to do this. And, we have neighbors who have sheep, as well. So there are plenty of opportunities for me once I learn this skill.”

After one day of shearing, Larsen realized how much she still had to learn.

“It’s definitely going to take all three days,” she admits, adding that she had zero experience shearing before the school began. “And they say it takes a thousand sheep to really know what you’re doing, so it’s going to take a while. But this has been a great place to get started. It feels like I’m going back to college.”

University of Montana-Western freshman Sawyer Evans is in college, but the shearing school just might provide the most valuable education he’ll receive. Evans grew up on a Montana ranch and has aspirations of shearing professionally. He was attending the school for the second straight year.

“Mike (Schuldt) kind of took me under his wing after this school last year and helped me shear a few here and there,” Evans says. “I’ll probably come to the school a third time. There’s always more to learn, and I can spend time trying to perfect each blow.”

Like Schuldt did, Evans would like to become proficient enough at shearing to hire on with a crew in New Zealand some day. Island life – at least for a portion of each year – sounds pretty appealing to the Montana teenager.

Like Schuldt did, Evans would like to become proficient enough at shearing to hire on with a crew in New Zealand some day. Island life – at least for a portion of each year – sounds pretty appealing to the Montana teenager.

“It would be a great experience,” he says. “But I know that I need to be a pretty good shearer before I can do that. Mike did that, and it was a great experience for him.”

While students spent most of the the three days hunched over sheep on the school’s newly constructed, elevated shearing platform, time was devoted to other important aspects of shearing. Topics covered included appropriate clothing, necessary tools and equipment, stretching, shearing as a business and wool handling.

Clothing

• Long tailed shirts that will stay tucked while you’re bent over are a must. Shirts that ride up your back will leave it exposed to the elements – which means cold in many parts of the country. If your back gets cold while shearing, then it’s guaranteed you’ll finish the day with a sore back.

• Choose clothing that wicks away moisture – such as sweat – to help keep you warm, dry and comfortable. Wool items are obviously a good choice.

• Moccassin-like shoes are preferred by professional shearers for their non-slip soles and because they allow for better use of your feet to keep the sheep in place during shearing. Ben Roeder found himself without his shearing shoes the first day of the school and chose to shear in his socks over wearing the muck boots he had with him.

• A simple web search will turn up a variety of sites that offer appropriate clothing for the job.

Tools and Equipment

• If you have plans of making a living as a shearer, buy the best tools possible from the start. A good handpiece will cost $700 or more.

“You might need to spend $1,500 in tools to get started,” Schuldt says, “but those tools will pay for themselves in a month and might last for years. It’s an investment, so don’t skimp on it.”

• Beware of used shearing tools. There are times when those new to shearing invest in great equipment only to find out a month or two later that shearing just isn’t for them. In such cases, practically brand new tools might be a steal.

More often than not, however, that tool’s up for sale because it wasn’t working for the original owner for one reasaon or another.