Fine Fleece Back East

Colyers Fill Niche with Merino Wool

KYLE PARTAIN

Sheep Industry News Editor

Waving in the wind just below the stars and stripes is a blue banner that reads, “Don’t give up the ship.” On most sheep farms, the flagpole’s second adornment might seem out of place. But not at Greenwood Hill Farm in Hubbardston, Mass.

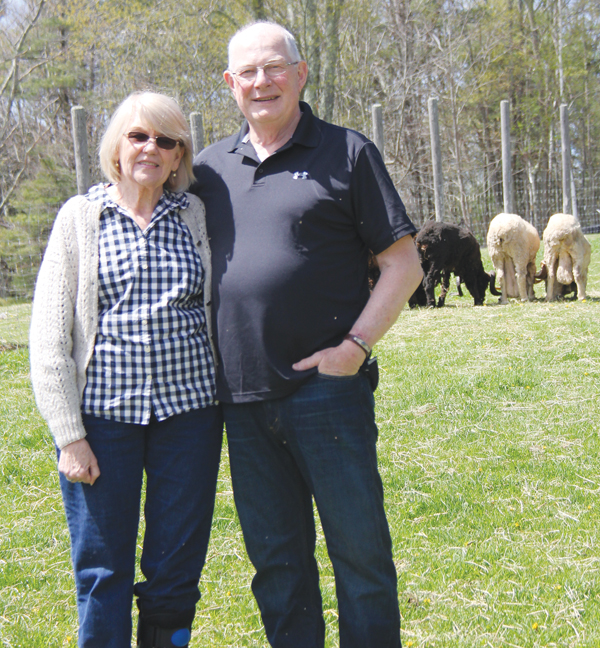

This is the home of retired Navy Capt. Tom Colyer, who spent 28 years living by such words in service to his country. But for nearly 30 years now, securing the farm has been just as big a priority as national defense. Like many parents, Tom and his wife, Andrea, have their children to blame – specifically their daughter, Jennifer.

This is the home of retired Navy Capt. Tom Colyer, who spent 28 years living by such words in service to his country. But for nearly 30 years now, securing the farm has been just as big a priority as national defense. Like many parents, Tom and his wife, Andrea, have their children to blame – specifically their daughter, Jennifer.

Shortly after the family moved to the historic house – built by Silas Greenwood in 1836 – she made friends among the area’s 4-H crowd and needed a livestock project. Up until that point, the farm had been home to one horse and a handful of chickens.

“The property was going to be taxed as building lots, so we had to do something to keep the tax bill down,” Tom explains. “To have it taxed as agricultural land, we needed just $500 a year in gross sales.”

So, the family created a chicken house and began selling eggs door-to-door as well as through a local goat dairy. That satisfied the state regulations until the sheep came along in 1987.

“The Merinos were my choice,” says Andrea. “I have an allergy to wool and it makes me break out in a rash. But I found that I can wear Merino wool without a problem. And, I could knit with it. So, we bought a registered ram and ewe out of New York and that’s how we got started in the Merino business.

“The first ewe we bred had mastitis and had no milk. So, we started off with a bang. The local vet had sheep and saved the day for us that first year.”

With no real sheep experience, the Colyers pushed forward to develop a flock that routinely won both in the show ring and in fleece competitions. A ribbon-covered wall of the old farmhouse is a testament to the success the family had before walking away from the show ring as Jennifer transitioned off to college and eventually started a family of her own.

“By 1990, we had 100 head or more on the place,” Tom says of the family’s 32-acre farm. “We had her flock and our flock, and they were different. She was showing her sheep, while all we wanted to do by then was show the fleeces.”

The sheep provided a shared family experience for the family’s youngest child.

“My bonding time with our two sons was rebuilding cars,” Tom recalls. “When they were getting ready to drive, we found the car they wanted and went to work on it. Jennifer wasn’t too interested in cars, so we got to know everything there was to know about sheep. She worked really hard around here because of the sheep.”

Tom applied his military training to the industry, serving on the boards of various industry groups, including the ASI executive board and now the American Lamb Board.

For Andrea, the wool was always the first priority.

“When she graduated and moved on, we really went back to focusing on the wool,” Tom says. “Andrea really wanted to be in the knitting yarn business, so that’s primarily what we do here. We sell it direct to the buyer by traveling around to the sheep and wool festivals and farmers’ markets.”

While the couple doesn’t sell yarn online, the sheep business does as well as it is supposed to do.

“We never planned to live off it,” says Tom. “But we wanted to find a way for the sheep to pay for themselves. That was the goal. We had two pensions from previous lives that paid for the house and for the kids to go to college.”

Joining the Mass Local Food co-op in recent years led to increased demand for lamb from the farm, which created its own issues given the long lead time necessary to grow Merinos. The Colyers have answered that demand with a unique arrangement in which they buy Southdowns from area producers and serve as a New England feedlot for finishing the quicker-growing sheep.

Joining the Mass Local Food co-op in recent years led to increased demand for lamb from the farm, which created its own issues given the long lead time necessary to grow Merinos. The Colyers have answered that demand with a unique arrangement in which they buy Southdowns from area producers and serve as a New England feedlot for finishing the quicker-growing sheep.

“We just bought the first group of the year last week,” Tom says in early May. “We got a call from a local producer who had a bunch of lambs. She sold a few, but she just doesn’t want to take those ram lambs to the auction or to the slaughterhouse. So, I go down and pick them up and pay her by the pound. We have five or six of these folks.

“Our arrangement allows them to continue to have lambs and run the operations they want to run, but we take care of the part they don’t want to deal with. It’s good for us because it gives us a more consistent lamb product because it takes twice as long to grow out the Merinos.”

Meat talk aside, the wool is still the first priority for the Colyers, who take their fleeces to Green Mountain Spinnery in Vermont for processing. The couple runs both white and black Merino sheep, producing four distinct colors of yarn that have proven popular through the years. In addition, the family sells sheep skins at each of its stops.

“A few years back at the Maryland Sheep and Wool Festival, we had a pelt that this couple was really interested in, but they just weren’t sure about it for the price,” Tom recalls. “They came back several times, but the last time they came back we’d already sold it. I told the guy, ‘We can’t do it here, of course, but I think the best way to sell those things is let people get naked and roll around on them to see how soft they are.’ He just looked at me and said, ‘Why didn’t you mention that a few hours ago.’ I guess if I had, he wouldn’t have debated about whether it was worth the price or not.”

Maybe it’s a good thing Tom is rarely in the couple’s booth in Maryland. He’s taken on an announcing job in an effort to indoctrinate festival attendees with sheep knowledge, and generally leaves the wool and pelt sales to Andrea.

“She’s the expert when it comes to the wool,” he says.