A Different Point of View

Opportunities (Not Challenges) Drive Oregon’s Reed Anderson

KYLE PARTAIN

Sheep Industry News Editor

Parked next to a still-born lamb, an eagle celebrates an easy breakfast. It’s a rancher’s nightmare for two reasons: first, a lamb is dead and, second, a predator has taken up temporary residence among the most vulnerable of his livestock.

Sheep producer Reed Anderson sits silently behind the wheel of his pickup, and I can’t help but wonder what he might thinking? Will he sell tickets to city slickers anxious to see an eagle. That could more than recoup the cost of the lamb and provide a new revenue source for the Oregon rancher.

“We try to turn every challenge into an opportunity,” he says. “The goal is to utilize everything we have to the best of our ability.”

“We try to turn every challenge into an opportunity,” he says. “The goal is to utilize everything we have to the best of our ability.”

Chances are that Reed doesn’t even see this morning’s encounter as a challenge. It isn’t a large enough blip in his day to warrant tackling. Instead, he drives close enough to scare off the eagle, collects the lamb and is back on his way. There are bigger opportunities ahead, and he’s already focused on those.

There’s a reason Reed has been chosen to serve in leadership roles with the American Lamb Board, the National Lamb Feeders Association and, most recently, ASI. The Region 8 representative to the ASI Executive Board has long been a leader in the industry.

The fourth-generation rancher certainly benefited from growing up in the sheep business, but those benefits didn’t include any land or sheep when it came time for him to set out on his own. Like many in the Oregon sheep industry, at that time he didn’t really own a thing.

“A lot of the producers in Oregon don’t own the ground they run on or the sheep they run on it,” he says. “A lot of guys are still doing that and are happy with that business model. I got started like that and was doing the same thing, but it was too thin a piece of the pie for me. My wife (Robyn) and I wanted a bigger piece of that pie, so we started buying sheep. We started buying land. We own about 1,000 acres and lease some too depending on the time of year, weather and other factors.”

For sheep producers, owning land in Oregon’s Willamette Valley provides two sources of income: grazing and grass seed. Stocking rates vary from two animals per acre to 20, reaching its highest point each spring as the valley’s pastures come to life.

“There’s always green grass somewhere around here, even in winter,” Reed says. “I’ve been doing this for 40 years and there were probably only two years where we had three feet of snow and a hard freeze that killed all of the grass. So, we don’t have to feed sheep around here very often.

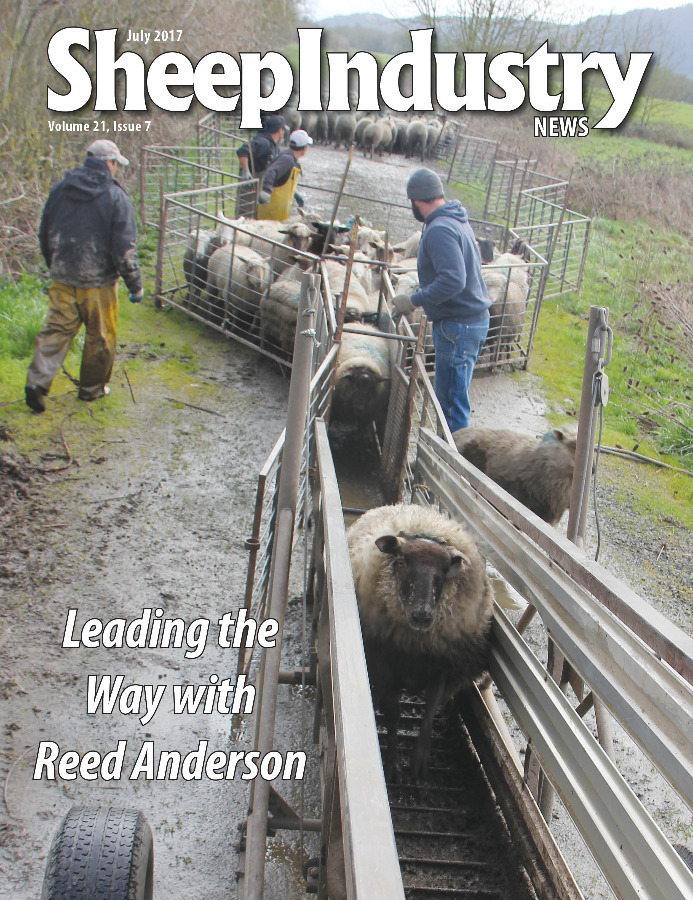

“In the winter, we try to find a place we can leave the sheep for a month or two or three. That’s pretty hard around here, and it’s all weather driven. There are times in the year when we’re moving sheep all the time. But we have portable corrals and the sheep are used to it. It actually works to our advantage because when they get to the plant and start going in, they just assume they are being loaded to go to another green pasture. They handle pretty well at the plant because of that.”

Taking ownership of his land and livestock, Reed encountered a new “opportunity.” He often found it difficult to get his lambs processed and had no control over scheduling. Meeting the situation head-on, he developed a plan to build his own processing plant.

“I’d thought about building a plant for years,” he says. “What I needed was to get to the point where I was financially sound enough to make it happen. I could really see that as a bottleneck for the industry, and with my own plant I could eliminate that bottleneck. There’s lots of great ideas out there that never get done just because of money. But you also have to be willing to put in the time and effort to make these things work. A lot of people just don’t want to work hard enough to make it happen.”

Kalapooia Valley Grass Fed Processing opened in 2013 and processes 250 of Reed’s lambs each week. Another 200 or so from area producers come through the plant during that time, as well. There’s also a cattle side to the processing operation.

“Those big packers are killing 1,500 lambs a week, so when you think of it like that, our operation isn’t all that big,” Reed admits. “But to come up with 400 to 500 lambs a week is a big challenge. Procurement is probably my main job. My sons, Jake and Travis, run the ranch and the plant on a daily basis, so sometimes people wonder what I do all day. A lot of it is networking.”

A former shearer, Reed has connections throughout the state’s sheep industry, and has found that involvement with groups such as the Oregon Sheep Growers Association and ASI play a vital role in connecting with potential customers and suppliers. But the success of the family’s three businesses (Anderson Sheep Company, Anderson Ranches and Kalapooia Valley Processing) relies on the hard work of the family and its employees.

“We pride ourselves on having good people, and that starts with the family,” Reed says. “My boys are the fifth generation to work in sheep, and it’s a blessing to have them around. We didn’t think that Travis would be here because he was slated to play baseball. But a knee injury changed those plans. Still, we were surprised he came back. He never really cared for ranching, and still doesn’t even though he’s good at it. But running the plant has been a great fit for him.”

Reed stressed to his boys that they weren’t required to work in the family business, that his first priority was for them to find a line of work they enjoyed.

“The hardest part about running the plant is dealing with an eight-hour work day,” Reed says. “Being farmers and ranchers, we’re used to working until the work is done. But anything over eight hours in the plant (which employs a U.S. Department of Agriculture inspector) brings financial consequences that we have to deal with. There’s no overtime pay in ranching, so that took some getting used to with the plant.”

In typical fashion, Reed takes such “opportunities” at the plant and turns them into win-win situations for the family business. In processing lambs, he ran into a fare amount of waste products that the local rendering plant wouldn’t take because of scrapie-related concerns.

“We compost that waste and spread it on the fields,” he says. “The secret for meat compost is that you need lots of fiber, and we’re in an area that has lots of fiber from the grass seed straw. We can take the bottom bales, the wet bales, the undersized bales and make them work for us, and they’re virtually free. We mix meat by-products, fat, bone, hides we can’t use with the straw and it makes wonderful compost. We’ve doubled the yields on our grass seed since we started using it. It would cost us a fortune to take that waste to the landfill, so we found a solution that works for us.”

Some people have a problem for every solution, but Reed seems to have a solution for every problem.

“I look for opportunities all the time,” he admits. “For some reason, I’ve always had a knack for that. When we built the plant, people said it took a lot of guts or that it was risky. I didn’t see it as a risk. I saw it as a heck of an opportunity.”