- July 2018

- President’s Notes

- Exports Drive Market for American Wool Producers

- Family Matriarch: Jeanne Siddoway

- IWTO’s 87th Congress Tackles Wool Sustainability

- NSIIC Budgets Funds for 2018 Grant Proposals

- Young Entrepreneur: Brady Campbell

- ASI News

- Around the States

- Obituary: Ernest “Bud” Gutzman

- Market Report

- Genetic Scrapie Resistance in Goats

- The Last Word

Family Matriarch

Jeanne Siddoway Recalls Lifetime in Sheep Industry

SYLVIA ALLEN

Special to the Sheep Industry News

Being the matriarch of one of the largest sheep ranches in Idaho has not been without its challenges for Jeanne Siddoway, who at 95 years old still makes candies and other treats for her family’s Peruvian shepherds for Thanksgiving and Christmas.

However, her biggest contribution to the sheep industry, she will tell you, are the sons she shared with her late husband, Bill, one of whom – Jeff Siddoway – is an Idaho state senator.

Thanks to modern conveniences life is easier now, but it did not begin that way when her husband Bill’s grandfather brought their first flock from Tooele, Utah.

Thanks to modern conveniences life is easier now, but it did not begin that way when her husband Bill’s grandfather brought their first flock from Tooele, Utah.

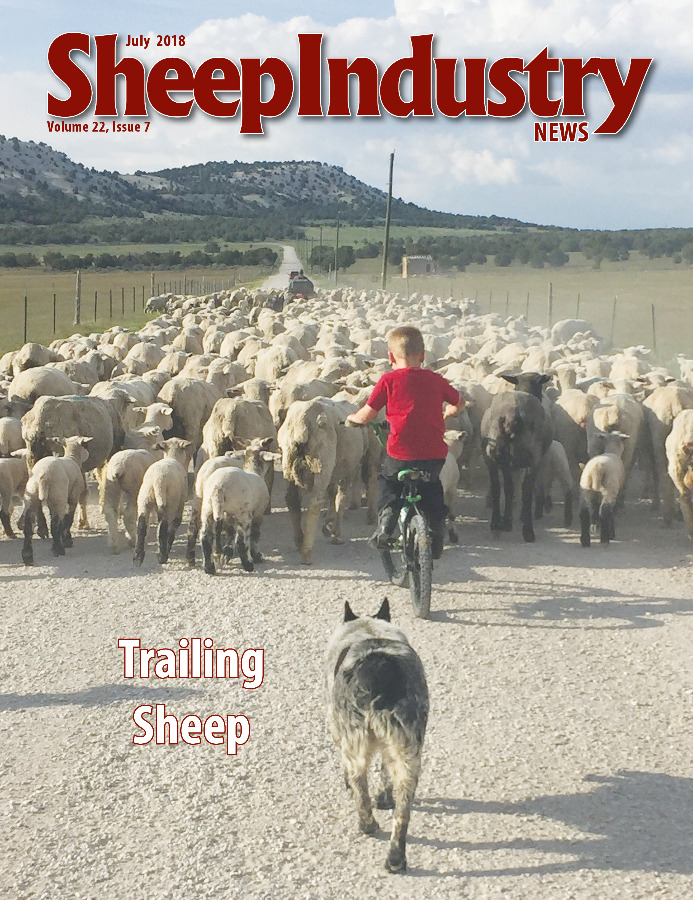

“We just trailed the sheep all the way here,” said Jeanne Siddoway. “We did have the railroad, but we didn’t have all the trucks that we have now to fill up with gas. At that time, they didn’t have as many sheep as they do now, but times were different. There were horses and buggies and water tanks on wagons pulled by horses and no telephones. So we didn’t know what was going on at a sheep camp until we got there.

“And we didn’t know if the hired man had made a trip with a load of water and if we needed to make a second trip. I think how much easier my husband’s life would have been had there been these cell phones and how much gas we could have saved. And maybe it wouldn’t even have taken as many horses and (as much) feed and all of those things.”

Nevertheless, the challenges of rearing three girls and three boys – one of whom died of kidney failure in his 30s – has not been easy for this lady who lives in St. Anthony, Idaho, where she has aged gracefully.

During the busiest time of the year for the family – lambing season – her daughter, Kathy, was diagnosed with polio when the child was about 18 months old. The toddler had to remain for a time in Boise for rehab at the Elk’s Children’s Convalescent Center.

“We had to leave her there then, of course,” said Siddoway, “because we had livestock and everything to take care of. We were lambing at the time, and so I was cooking for the crew. It seemed like that was one of the hardest things we ever did was to leave Kathy down there crying, but it didn’t take long for her to make friends.”

Eventually the doctors told them they could bring Kathy home if they had a house with stairs, which during the 1940s and 1950s were perhaps an early form of physical therapy; the polio had affected one of the child’s legs.

“With our help, we could see that she went up, one step at a time,” said Siddoway, who still lives in that 15-room home. “So we had steps to get into the stairs, steps to get up the stairs, steps to get down to the basement. Every place you went in this house, you had steps. But it was great for Kathy.”

Nowadays though for Siddoway’s benefit, railings have been installed on all those stairways. In fact, near one of those railed stairways lies a four-inch spiral binder loaded with candy recipes. Siddoway’s culinary skills were not limited to cooking for the crew during the lambing seasons. In her earlier years, she took a college course in nearby Rexburg, Idaho, where she learned from Florence Manwaring, owner of Florence’s Exquisite Candies AKA Mom’s Kandy Kitchen, how to make “every kind that she puts in the candy box.”

Her age might keep her from doing all that she would like to do now, but it doesn’t prevent her from enjoying visits or phone calls from friends and family.

“I now have what’s called ‘essential tremor,’ which hinders me from doing a lot of things,” she said, adding, “my eyes aren’t as good as they used to be.”

Adversity is nothing new to Siddoway, who besides dealing with her own family adversities, has seen her family face threats to the wool industry and to their livelihood. Together they have weathered predators, politics, product depreciations and the weather itself.

“We’ve always had a problem with predators,” she said.

Her daughter-in-law Cindy Siddoway said that they lost 176 sheep in one night in August 2013 when wolves got the sheep on the run, causing them to pile up on one another and die of suffocation. The family must always be on guard to prevent disease from decimating their flocks, too.

Given their flocks’ 50-mile grazing proximity southwest of Yellowstone National Park, the Siddoways were impacted financially when larger Canadian grey wolves were introduced in 1995 to replace smaller Northern Rocky Mountain wolves. In February 2014, the Sheep Industry News reported that her son Jeff – a fourth-generation sheep rancher – had lost $30,000 to $50,000 annually in the eight prior years.

Political and governmental affairs have also affected the Siddoway’s livelihood, too, and not always with positive results.

“It seems like competing interests are always trying to take our range for something else,” said Siddoway wistfully. “At one time we owned that pasture land where they put the INL (Idaho National Laboratory). And what did they pay us? Hardly anything for that. And then, a few years later, they were paid more for it. They got a lot of acres from us. Politics have always been a part of the sheep business.”

As to the industry’s product depreciations, Siddoway expresses disappointment.

“The wool market hasn’t been worth a darn,” she said. “People just kind of quit wearing beautiful wool clothes. You couldn’t buy them any more even if you could afford them. You can’t buy a Pendleton reversible skirt anymore. And I kind of liked the reversible ones because it gave me two skirts in one. They’ve always looked good and I’ve always felt good in them. I’ve worn Pendleton since I was in high school. My first Pendleton skirt was a yellow and green plaid and I wore that for years and years until I started putting on some weight around the waist and then I had to give it up.”

Lamb imports from Australia and New Zealand have also hurt the Siddoway’s efforts to market their lambs for food.

“They can sell it and ship it cheaper than we can sell our own right here,” said Siddoway. She said that most of their lamb for consumption is sent to U.S. metropolitan areas in the East, where the market has risen.

In an effort to market their wool, Cindy – with her daughters and daughters-in-law – has been instrumental in starting the Siddoway Wool Company, which produces heavy woolen blankets depicting scenes of well-known features of the area, including the Grand Tetons.

Finally, weathering the weather itself has taken its stressful toll on the family. In her family album is an account of a high mountain blizzard sheep rescue that occurred when 400 sheep became separated from the flock.

Siddoway’s husband, Bill, set out with his pack horse and his dog to find them just above the timberline. Returning them to the flock, they encountered fog so dense that Bill could hardly see his horse’s head, a ledge that prevented him from getting down the mountain until he could carefully guide the lead sheep to safer ground, and boots frozen solid with ice the morning after he slept in a tent at a hunter’s camp.

Despite her adversities of weather, politics, predators and product depreciations, Siddoway still enjoys guests, especially those at the family’s elk and bison hunting preserve, Juniper Mountain Ranch, near St. Anthony, Idaho, where guided hunts for free-roaming elk and bison attract folks from throughout the United States. Their clients occasionally purchase one of the woolen blankets as a souvenir of the trip.

Some years ago, Siddoway would prepare little candy boxes for clients to tuck into their suitcases, too. But after a time, that became overwhelming, she said. She still enjoys going to the ranch to meet the guests.

Upon first meeting her a guest might ask, “And you must be Mrs. Siddoway?” She has been known to respond, “I am THE Siddoway.”

Indeed, her car’s license plate says “Sheep 1.”