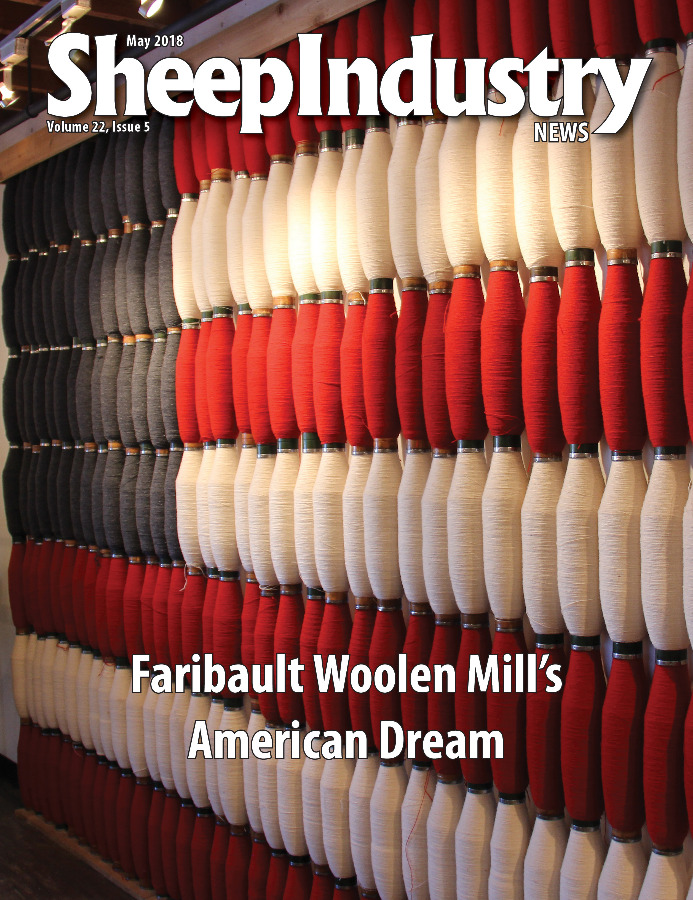

An American Dream

Faribault (Minn.) Takes Pride in Rejuvenating Factory, Brand

There’s a fine line between a good investment and a money pit, and Paul Mooty was trying to figure out where Faribault Woolen Mill fell as he tiptoed his way through toxic chemical residue on March 8, 2011.

He was along for the ride as other potential investors toured the property that sits about an hour south of Minneapolis off Interstate 35. The mill had been closed for approximately two years at that point. Had he driven his own car, the tour would have come to an abrupt end.

He was along for the ride as other potential investors toured the property that sits about an hour south of Minneapolis off Interstate 35. The mill had been closed for approximately two years at that point. Had he driven his own car, the tour would have come to an abrupt end.

“There had been a flood the fall before and the lower level had taken in eight or nine feet of water,” Mooty recalls. “There was chemical residue everywhere and they told us not to touch anything. It was bad. It seemed senseless.”

As luck would have it, Mooty likes a good challenge. After spending a couple of hours in the historic property, he couldn’t shake the sense that Faribault offered a unique opportunity. But buyers from Pakistan were interested in the mill’s equipment – some of which dates to the early 1900s. The clock was ticking.

“Sometimes a short time frame is good,” Mooty admits. “I had practiced law and could have written 10 legal pads about why I shouldn’t do this. But what I quickly realized is that if they started to dismantle the mill, then it would probably never be put back together again.”

Mooty joined with his cousin, Chuck, and jumped into the wool textile business with both feet. A crew of five opened the door for business again on July 5, 2011, and with it rejuvenated a 153-year-old business that has long been a source of pride in this central Minnesota town.

“We’re not the biggest business or the biggest employer in town by any stretch, but the community has always taken a lot of pride in the mill,” Mooty says. “We are a business, but we’re standing on the shoulders of the Klemers and the Johnsons, who ran this as a family business for so many years. There is a mission component here, and that is to create a viable, long-term, sustainable model so that people 100 years from now still recognize and understand the value of the Faribault name.”

It’s been estimated that at one time as many as half of the wool blankets in the United States were produced by the Faribault mill. Soldiers have carried them into battle across the globe, energetic children have been known to nap under them and they’ve been passed from one generation to the next as family heirlooms.

“That’s why we decided to take a risk on it,” says Mooty. “The purchase of buying the assets and the building wasn’t really a lot. The unknown was the building. We knew we could bring it back to life, but we didn’t know how much that might cost. But you don’t find a lot of 150-year-old companies lying around looking for a new owner. We had a head start in the race because we had a brand name with a long history.”

As is the case with many American companies, Faribault’s storied history took a downtown as manufacturing moved offshore in search of cheaper labor. That led to the mill’s closure in 2009, and was why many investors weren’t anxious to jump on board in the years that followed.

“The owners had had plenty of tire-kickers, but no one had followed through,” Mooty said. “That’s why they were willing to sell off the equipment to a group from overseas. They didn’t give us much time to make a decision. If we’d had six months or a year to really think about it, we might have talked ourselves out of the decision to buy the company. This thing was so close to being gone. I’ve often said that we underpaid for the name and everything else was free. The name was the most valuable asset we bought. Had this just been Paul and Chuck’s blanket company, nobody would have cared what we were doing.”

But plenty of people did care. Longtime employee Dennis Melchert served as guide that fateful day when Mooty toured the facility. He promised that the company’s loyal customers would return “as soon as the open sign goes up.”

Fortunately, customers still associated the Faribault name with quality, and a rising interest in buying American-made products helped spur the company’s resurgence. Millennial buyers in particular, are interested in the story behind the product as much as the product itself. Faribault had a story to tell, and a good dose of free publicity helped to share that story outside of the company’s Minnesota stomping grounds.

“NBC came to us and wanted to do a piece on the Sunday Evening News in the fall of 2011,” Mooty recalls. “It was a really nice piece that was a couple of minutes long. We had in excess of $100,000 in online sales by the next morning. We were only selling a couple of hundred bucks a day at best on our website back then. We got phone calls, letters and emails from people all over the country. We could tell from the reaction we got that our story really resonated with people and they were excited about it.”

Pieces on ABC, CBS, Fox and MSNBC followed. The company appeared on the front page of USA Today and in magazines as far away as England and Japan.

Faribault’s first big contract came with J.C. Penny in 2012 as part of the store’s made in America line. For a while, the contract provided the bulk of the company’s orders. But slowly, Mooty and his staff have been able to diversify. Online orders, boutique retailers, military contracts and corporate gifts all play a role in the company’s bottom line these days.

Thanks to a Department of Defense contract, blankets routinely end up at the U.S. Military Academy in West Point, N.Y., aboard ships in the U.S. Navy and even halfway around the world with the Iraq and Afghanistan militaries.

“It’s nice to have that range of business,” Mooty says. “That wide range of channels has served us well through the years. It means we don’t have to rely on one part of the business to be successful. What we’ve found is that we have a lot of great ingredients here, but we’re constantly looking for that right mixture to make it all work.”

While the plant still has an ancient scouring line in the basement, Faribault purchases clean wool through Chargeurs to create a line of products that is mostly 100 percent wool.

“When we were in the process of buying the mill, there was a consultant who had advised the previous board of owners. He told them to get back to focusing on the wool textiles, and that there was a good business there where they could be successful. They chose not to take his advice and things went bad,” Mooty says. “We’ve chosen to follow that advice. We have done a little bit with cotton – mainly a lighter spring line we wanted to create. But wool is what we do here. We don’t see any reason to get away from that.”

“When we were in the process of buying the mill, there was a consultant who had advised the previous board of owners. He told them to get back to focusing on the wool textiles, and that there was a good business there where they could be successful. They chose not to take his advice and things went bad,” Mooty says. “We’ve chosen to follow that advice. We have done a little bit with cotton – mainly a lighter spring line we wanted to create. But wool is what we do here. We don’t see any reason to get away from that.”

Sticking to tried and true methods applies to the company’s equipment, as well. While you’ll find newer looms and other machinery that Mooty has purchased, there’s also plenty of original equipment still in operation.

“What we found when we took over is that the older the equipment, the easier it was to get up and running. If it needed a chain or a belt or a motor, we could fix it pretty easily,” he recalls. “Anything that came along a little later and had a computer board or chips in it, was more of a problem to find replacement parts for. But all of the equipment that was in the building when we purchased it is still here. The key to that was finding people who had worked here in the past and bringing them back. By the end of the first year, we had 40 employees and 35 of them had experience working in this building before I owned the company.”

One of those – 83-year-old Mary Boudreau – has worked for the company longer than Mooty has been alive. The company took her 63 years of experience to Washington, D.C., when President Donald Trump hosted a Made in America Product Showcase last summer at the White House.

“She certainly deserved the opportunity to go and represent Faribault,” says Mooty, who got a brief meet-and-greet with the President at the showcase. “These are the folks who helped get this thing back on track. I didn’t come into this with any experience in wool textiles. I’m learning every day, so I’ve had to lean on the experience of our employees along the way.

“I think that we’re supposed to be here, so we’re going to keep hacking away at this thing and doing our best to get it right.”