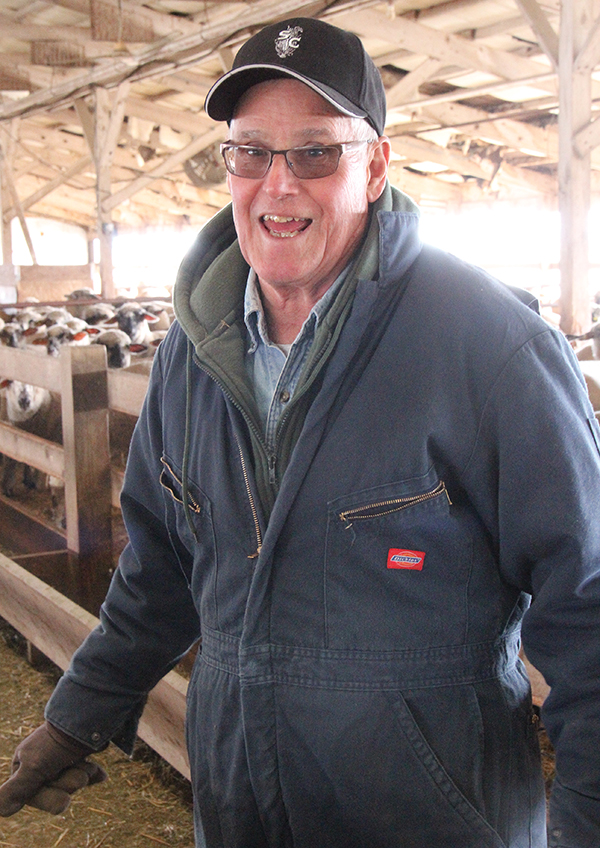

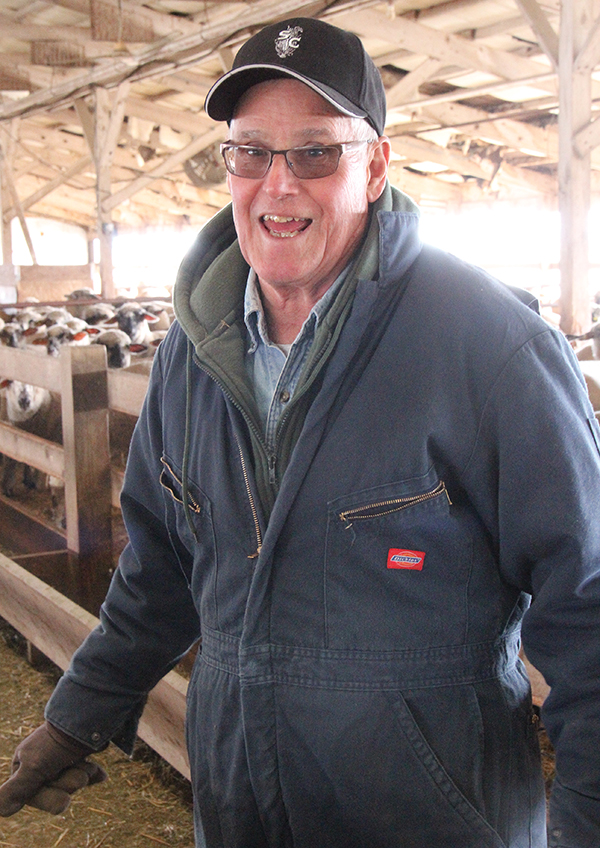

Skyline Turkey Farm in Danville, Ohio, has plenty of skyline and lots of farm, but is decidedly lacking when it comes to turkey. Instead, the barns are full of lambs and a growing ewe flock.

“Strangely enough, the turkey industry pulled away from us,” says Don Hawk. “They closed a plant in Zeeland, Mich., that was our closest delivery point. So, we had to look for something else to do. We put our first feeder lambs in 20 years ago last September and we’ve been feeding lambs ever since.”

“Strangely enough, the turkey industry pulled away from us,” says Don Hawk. “They closed a plant in Zeeland, Mich., that was our closest delivery point. So, we had to look for something else to do. We put our first feeder lambs in 20 years ago last September and we’ve been feeding lambs ever since.”

The move fulfilled a prophesy of Don and Janet Hawk’s son, Delbert, who had raised sheep for 4-H and grew his flock to 40 ewes by the time he graduated high school. That flock disappeared fairly quickly, but Delbert told his dad at the time, “When you quit raising turkeys, I’m going to fill those barns with lambs.”

That was the family’s only exposure to the sheep industry before diving in head first in the 1990s.

“We went through a shakeup with the turkey processor we were selling to and they started juking things around on us. We wanted to diversify the farm, so we put up a hydroponic green house big enough for 850 tomato plants. When we looked at it, we either had to diversify the farm or one of us had to go and get a job in town. So, we diversified the farm. The tomatoes were a really good program back then, but that was before NAFTA. Once we were competing with tomatoes out of Mexico and Canada, it wasn’t as good a market for us.”

Looking to get out of the turkey business and be less dependent on tomatoes, the family needed a new income source that would utilize the farm’s existing barns. And that’s how they became lamb feeders. Skyline Turkey Farm – Don says it’s too expensive to change the name – houses up to 1,500 lambs at any given time. The Hawks also raise some cattle and farm 600 acres of row crops: corn, beans, wheat, bale straw and hay.

“We thought we could handle sheep because Janet and I had both been around livestock all our lives,” says Don. “More than anything, we wondered how people in the sheep industry would accept us, since we were the turkey guys looking to get into sheep. We were outsiders, but that didn’t last long. It felt pretty good when we sold our first set of lambs at the sale barn and the processor came back and asked if there were any more of those turkey lambs.”

Skyline Turkey Farms established itself quickly with a processor who sells into fine restaurants along the East Coast. The partnership has been a good one for both sides.

“We don’t just open the gate and load lambs,” Don admits. “We work them and look to give him a consistent finish. We’re pulling the top end off every time. He wants a lot of cover on them – more than the industry talks about. That extra cover keeps the meat pinker and fresher. A lot of that cover ends up in the waste can, but that’s the way these chefs want it. He likes a 135 to 145-pound lamb. I call it a yield grade 3, but he calls it a high 2. Either way, it takes a lot of corn.

“The very first lambs we put in, we had to do it on the fly. We put in 350 that first week and a week later we put in 350 more. We had to prove ourselves a little in that we could handle the lambs and produce the kind of product that processor wanted. We were fortunate to get all of that accomplished with that first set of lambs. I knew right away that this wouldn’t work if we were finishing lambs and taking them right back to the sale barn. We couldn’t sustain a plan like that. We needed a working agreement with someone – like we had when we were raising turkeys – so that we could all be profitable. We were blessed to have that happen early on in the process.”

The biggest problem in recent years, however, has been finding feeders to buy. The family owned its own turkeys, and continued to buy its own livestock as it moved into feeding lambs. Loads of sheep came in regularly from South Dakota, Nebraska and Kansas. There were occasional lots from California or Texas, but the trucking costs can add up quickly when trying to get sheep all the way to central Ohio.

“We’re not as big as a lot of those feedlots out West, but we’ll feed 2,500 lambs a year,” says Don. “We got to a point where we were having a hard time finding the numbers. My son, Delbert, wants to take the place over someday and keep running it, so I told him he would need to consider developing a ewe flock so we can produce some of our own lambs.”

Some 200 ewes now share space with the feeder lambs as the family looks to build a genetic plan that will support accelerated breeding. Three lamb crops in two years would be ideal, Don says.

“We probably won’t ever produce near what we feed out, but we’re growing in that respect. I’m not sure we can support more than 300 ewes with the barns that we have, but that will be up to the next generation to decide at some point. If he wants to build more barns and run more sheep, that will be his decision.”

Feeding sheep inside solves two problems for the Ohio producers: predators and parasites. Coyotes, domestic dogs and black vultures are a problem in the area during calving time, and Don figures the problem would be even worse if he had sheep lambing outside.

“We dramatically reduce both of those potential problems just by keeping the sheep inside,” he said. “This is what works for us. We were blessed to have the buildings. If we’d had to pay for them out of feeding lambs, it would have been tough.”

“We dramatically reduce both of those potential problems just by keeping the sheep inside,” he said. “This is what works for us. We were blessed to have the buildings. If we’d had to pay for them out of feeding lambs, it would have been tough.”

So far, adding the ewe flock hasn’t really cut into the farm’s feeding capacity.

“We just have to manage the barns a little different,” Don says. “The barn we’re using for our brood ewes was originally our startup barn when we trailered lambs in. Now we’re just working with the finishing barn. We can still keep 800 to 900 lambs on feed and bring in another 400 to 600. We just have to manage it and be careful with our biosecurity management.”

Now a veteran lamb feeder, Don was elected to serve on the board of directors for the National Lamb Feeders Association during the group’s meeting in January in New Orleans.

“Steve Schreier (an NLFA past president) had been trying to get me more involved the past couple of years,” Don said. “So, I put my hat in the ring. I’m not afraid to share my opinions on feeding sheep.”

With two decades of experience feeding lambs, Don certainly has a lot of insight to offer the American sheep industry.

“Strangely enough, the turkey industry pulled away from us,” says Don Hawk. “They closed a plant in Zeeland, Mich., that was our closest delivery point. So, we had to look for something else to do. We put our first feeder lambs in 20 years ago last September and we’ve been feeding lambs ever since.”

“Strangely enough, the turkey industry pulled away from us,” says Don Hawk. “They closed a plant in Zeeland, Mich., that was our closest delivery point. So, we had to look for something else to do. We put our first feeder lambs in 20 years ago last September and we’ve been feeding lambs ever since.” “We dramatically reduce both of those potential problems just by keeping the sheep inside,” he said. “This is what works for us. We were blessed to have the buildings. If we’d had to pay for them out of feeding lambs, it would have been tough.”

“We dramatically reduce both of those potential problems just by keeping the sheep inside,” he said. “This is what works for us. We were blessed to have the buildings. If we’d had to pay for them out of feeding lambs, it would have been tough.”