- January 2019

- President’s Notes

- LMIC: Lamb Prices Capped by Frozen Stocks

- Jack Ewing Wins Wool Excellence Award

- Barnhart Bliss

- WS Keeps Crews Sharp with Annual Training

- San Angelo’s Fiberglass Sheep Flock

- Market Report

- Around the States

- Obituary: Willo Jean Brown

- Obituary: Truman David Julian

- Oxfords to Award Foundation Flock

- The Last Word

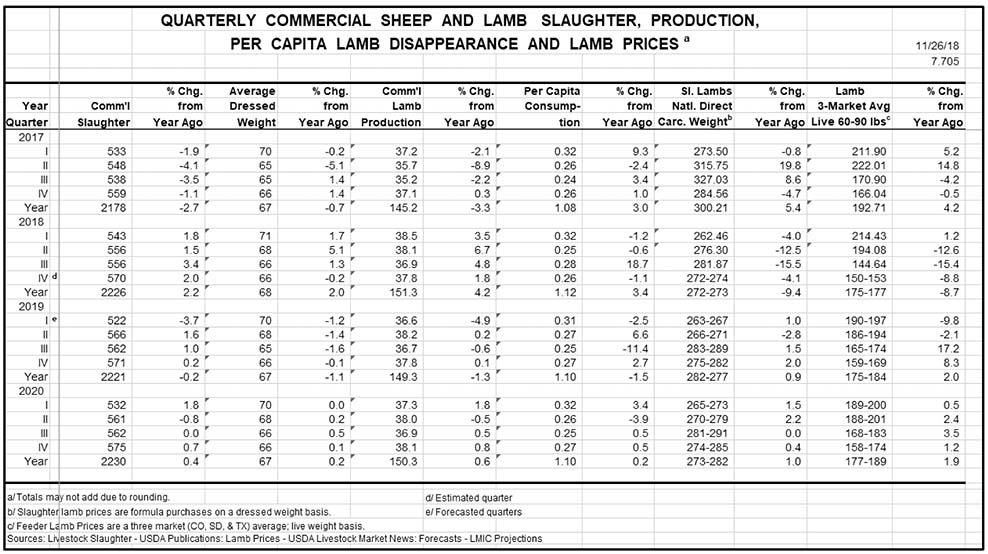

LMIC Analysis: Lamb Prices Capped by Frozen Stocks

LIVESTOCK MARKETING INFORMATION CENTER

Lamb and mutton in cold storage (frozen stock) is once again approaching levels seen in 2015. The July 2018 Cold Storage report indicated lamb and mutton frozen stock surpassed 42 million pounds, the highest tonnage of the year and similar to burdensome levels in 2015. The overhang has been boosted in part by higher slaughter numbers and heavier dressed weights in the domestic market, but imports also have likely played a role.

Across the lamb complex, prices have been below a year ago both on the live animal and the meat side. The lowest weekly price (carcass base) in the 2015-16 period was $256.77 per cwt. in April 2016, which was set after reaching highs of $315 to $320 per cwt. that previous summer. Earlier this year, carcass lambs were near that price at $258, but have since come back up some. The lamb cutout (wholesale meat carcass equivalent value) has remained above the lows of 2015, but struggled in the summer quarter to reach above a year ago. Amidst established consumption patterns in the United States, it seems unlikely lamb stocks will work themselves down in a swift fashion – which will likely lead to capped prices in 2019. After that, slaughter lamb prices are expected to improve in the next year to year-and-a-half with 2020 averaging 1 percent above 2019.

U.S. Inventory of Sheep and Lambs

As of Jan. 1, 2018, the United States sheep and lamb inventory fell 20,000 head, or by about half a percent, according to the annual U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service survey of producers. In the last five years, total sheep inventory has been between 5.2 and 5.3 million head. Importantly, as of Jan. 1, 2018, the survey reported larger a drop in the national number of ewes kept for breeding of 40,000 animals, or 1.3 percent. That is on the heels of 2017, which also posted a year-over-year decline in the ewe count of nearly 2 percent. Declines in ewes one year and older were across a variety of states. The largest increase was in Texas, which was up 25,000 head. The largest declines were in Wyoming and California, down 15,000 each. Total market lambs climbed 20,000 head on slightly higher lambing percentages in 2017.

In the last few years, it appears that the erosion in the size of the national breeding flock has been the result of relatively few ewe lambs kept for breeding purposes. Mature ewe disappearance, slaughter levels and exports to Mexico, as a percentage of the breeding flock have been on the downtrend. If the Jan. 1, 2019, breeding flock inventory continues to slip compared to a year earlier, that trend will likely again be the driver.

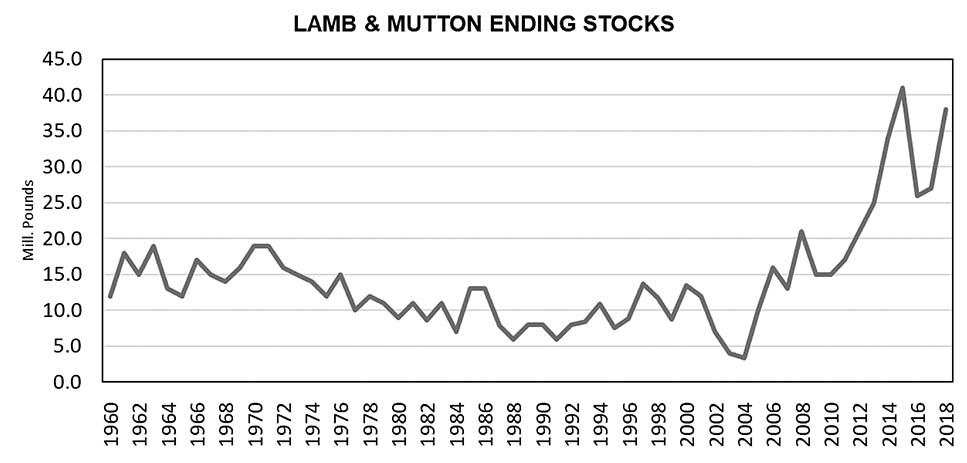

Cold (Frozen) Storage Problematic

The latest frozen stocks data (October 2018) showed lamb and mutton 24 percent above 2017’s level at 39 million pounds (product weight). That was 26 percent above the five-year average and the second highest month so far this year. Critically, that tonnage is equivalent to nearly 17 weeks’ worth of domestic production and 10 percent of annual disappearance. In comparison to other red meat categories, currently, beef stocks also are considered high but represent less than one week of domestic production and 2 percent of projected 2018 annual disappearance. Pork in cold storage was below a year ago in October and represented just more than one week’s domestic production and stands at 3 percent of 2018 projected disappearance.

Increases in lamb consumption are typical in the fourth quarter. However, American consumption patterns are small relative to the overhang that a few months will do little to work down stock levels. At the end of this year, stocks are expected to be the second highest on record, surpassed only by 2015.

Some of this situation is reflective of changing consumption patterns. In the 1960s, United States per capita consumption was more than 4 pounds per person on a carcass weight basis. Since 1975, lamb and mutton consumption never rose to more than 2 pounds per person and in the last decade, consumption has hovered around 1 pound per person. Ending stocks averaged 15 million pounds from 1960 to 1975, equivalent to 2 percent of domestic production. From 1976 to the 1990s, stocks were even smaller – about 9 million pounds – but the domestic industry also significantly contracted.

Annual domestic production fell by half compared to the 1960-1975 average. Still, the ending stocks increased versus production, representing 3 percent of production. Lower stock numbers existed in the early 2000s, as well, but started rising again sharply since 2005. During this same timeframe, domestic production continued to fall, and imports rose. Through the last 10 years (2017-2008) ending stocks averaged 24.2 million pounds, while domestic production continued to shrink. Average ending stocks from 2017-2008 crept to 15 percent of annual production. In 2018, that ratio will be 25 percent.

International Trade

The United States exports a small percentage of its lamb and sheep meat production. But, the United States imports more lamb and mutton than is produced domestically. Almost exclusively, imports are from Australia and New Zealand. For the last couple of years, Australia has faced severe drought which has led to higher cull rates and increased slaughter. That should change when Australia turns to a rebuilding phase. Weather reports have been favorable in October – but it is too soon to tell – although lamb imports in September (most recently released trade data) have slowed. Australian imports of lamb in September were down 15 percent compared to 2017, the second month in a row of year-over-year decline. This is following four straight months of year-over-year gains above 20 percent. Year to date, United States imports of lamb from Australia are up 6 percent. Imports of New Zealand lamb were also down in September. That month’s product from New Zealand has been running behind last year’s by about 3 percent. Still, the high levels of imports shipped earlier this year puts total United States imports of lamb above last year by 5.2 million pounds.

Imports of mutton from Australia have been much stronger. Year-to-date total imports is 38 percent higher than the prior year. Australia has shipped 21.3 million pounds more mutton through the first nine months on the year. New Zealand mutton exports – similar to lamb – are down 36 percent compared to a year ago. The question remains how much of this product is ending up in cold storage. The cold storage report does not break out the imported product and domestic, nor does it distinguish between lamb and mutton.

On the export side, the United States primarily exports lamb and mutton to Mexico and Canada. September lamb exports were up 85 percent on that month alone. However, it was not sold to the usual major destinations of Canada or Mexico. United States year-to-date figures increased by 34 percent, driven primarily by gains in shipments to Mexico, up 44 percent. Canada has largely been absent from the marketplace this year.

Mutton exports are down 2 percent so far this year, with large declines in volume showing to both Mexico and Canada. Mexico purchases are down nearly 50 percent through the first nine months of the year while Canada is down 39 percent. Shipments to other countries have been higher, up 43 percent. Although September showed mutton exports to all destinations were down 65 percent.

The United States consumes relatively little mutton products, but tends to export those items to other destinations. The combination of the large increase in mutton imports and the absence of mutton exports could imply that some of the overhang in cold storage is in fact mutton that normally would have been shipped elsewhere. That would be a positive for the American lamb market as these goods are not substitutes for the domestic consumer, but it also seems unlikely suppliers are storing mutton in speculation for more robust demand at a later point in time.

Market Outlook

Lamb slaughter from January through the first week of November is up 3 percent above a year ago. Lamb weights this year have been heavier, but in recent weeks those gains have moderated. Last year through the first 44 weeks of the year, lamb dressed weights averaged 68.5 pounds. This year, the average is 70.5 pounds. Higher volumes and weights have added to cold storage levels, but in recent weeks dressed weight data has fallen over the last four weeks, losing 2 pounds in a single week. In the latest week of this writing (week No. 44), average dressed weights were 66 pounds – 2 pounds higher than lambs slaughtered the same week last year.

Burdensome cold storage levels are expected to dampen prices as well in 2019, limiting any upside price potential gained from tighter predicted supplies caused by a slight reduction in ewe inventory. However, one positive note has been the inventory of lambs in Colorado feedlots – the largest lamb feeding state – slipped lower year-over-year in October and November.

Higher feedlot inventories put pressure on lamb prices in 2018, but October and November saw those inventories slip to 9 percent and 8 percent below a year ago, setting up next year to be in a better position for positive lamb price gains.

This on-feed pattern is almost the opposite of the on-feed inventory cycle of 2017, when the year ended with 12 percent more lambs on feed than the previous year and those increases carried most of the way through 2018, driven by drought conditions. A contraction in the number of lambs in feedlots should help slaughter lamb prices as early as the first quarter of 2019. In turn, feeder lamb prices should benefit from overall inventory contraction in the ewe flock as well as lower on-feed supplies. However, feeder lamb prices are not expected to improve until late in 2019.

Expectations are for imports of lamb to moderate with the dissipation of the drought in Australia. Even if drought persists, the bulge in culling has likely already happened. The three-month rainfall index shows significant improvement after a wetter than normal October. Rebuilding of the Australian flock will take time.

Meat and Livestock Australia’s forecasts are for sheep slaughter to moderate in 2019 after two years of increased slaughter rates. Australian sheep slaughter in 2018 is estimated to be 23 percent above a year ago. In 2019, it’s expected to pull back 27 percent along with lamb slaughter, which should slow the rate of imports into the United States.

Domestic slaughter is expected to decline slightly in 2019, leading to nearly a 1 percent decline in commercial production compared to 2018. The demand profile for lamb is expected to remain similar to previous years. By 2020, cold storage levels will have dissipated some, and the lamb crop should return to a more normal lambing percentage. Market prices in 2020 of slaughter and feeder lambs are forecast to up-tick by just more than 1 percent.

LMIC forecasts, as of late November, are in the table below.